Editor’s note: In honor of the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, the Telegraph Herald will be publishing a series of articles about how the groundbreaking 19th Amendment impacted the tri-states, as well as some of the key residents involved. This is part two of our series. Look for our next installment on Tuesday, May 26.

When the founding members of the Northern Iowa Woman Suffrage Society attended the Grand Women Convention in 1869 in Galena, Ill., they already had solid resumes, at least according to the rules of Victorian Dubuque society.

They were wives of lawyers, mayors, Iowa legislators and merchants. The lone single woman among them was a teacher at Dubuque Senior High School. Some had prestigious New England pedigrees. They had more than 20 children between them. They were well-respected and received their fair share of invitations to social events and parties.

What they didn’t have was the right to vote, earn money, buy or sell property or make decisions regarding their life choices. Despite their intellect and interests, the census listed their occupations as, “Keeping House.”

Mary Newbury Adams, Lucy Robinson Graves, Henrietta Johnson Wilson, Rowena Guthrie Large, Laura Goddard Robinson and Edna Snell co-founded the first suffrage association in Iowa. Their initial meeting took place on April 17, 1869, at Wilson’s home on Locust Street.

Suddenly, whether intentionally or not, the women added “radical” to their resumes.

The Chicago Tribune reported that “the masculine element in Dubuque was in a flutter on account of these goings on.”

Perhaps some of the husbands agreed with their wives. Or maybe there were heated arguments behind closed doors. Most likely, there was a rescinding of social invitations and awkward meetings with acquaintances.

Graves’ husband, Julius, was a former mayor who was serving as an Iowa state representative. Adams’ and Robinson’s husbands, Austin and Frank, were law partners. Wilson’s husband, David, also was a former Dubuque mayor and had served as Dubuque County Attorney and as an Iowa state senator. Large’s husband, William, was an affluent merchant.

With or without their support, the women were making waves with their activities. A correspondence committee began writing to like-minded women in other communities. By the end of 1869, women in Monticello and Algona, Iowa, also had organized suffrage groups.

Despite the quick organization of the group, the wheels of progress turned slowly.

“I was struck by how long the women’s suffrage movement took to develop in Dubuque,” said Michael May, adult services librarian at Carnegie-Stout Public Library, “and how controversial it was, even among women.”

“Men and women alike took a stance on suffrage,” said Cristin Waterbury, Director of Curatorial Services for the Dubuque County Historical Society. “Some men supported it, some did not. Some women supported it, some did not.”

In October 1872, an editorial appeared in the Dubuque Herald by a local female resident.

She concluded: “I go sometimes to hear whatever lights the woman’s suffrage movement sends out to shine, and can admire whatever is brilliant, but my admiration so far has not been exalted so often as to have the thing become monotonous … I am Mrs. William Bryant, wife of the well to do merchant, William Bryant, and am more happy in being thus designated than if I were known as ‘Maud Stanly Fairchild Bryant,’ the lecturer, and public opinion knows not whether she has a husband or not.”

In 1882, news of a suffrage meeting in Des Moines was published in the Herald, along with some editorializing by a staff writer.

“It is presumed that all women who have no children to care for; old maids of mature years; spiritualists; wives of men who are compelled to sew their own buttons on their garments and who are forced to cook their own meals; termagants and superannuated femininity generally are expected to be present.”

Rumors began to fly that the suffrage movement was far more radical than just seeking the vote.

A New York suffrage leader, Victoria Woodhull, began speaking about greater sexual freedom, leading to the accusation that suffragists were promoting “free love.”

Suffragist Amelia Bloomer also promoted dress reform, seeking less restrictive clothing in the days of tight corsets and wide hoop skirts.

“She wore pants that became known as bloomers in an era when women simply didn’t wear such attire,” Waterbury said.

But most were focused on securing the vote.

Annie Savery, a Des Moines suffragist, wrote in the Herald in September 1871, “We disclaim any participation in, or sympathy with, any other organization, state or national, leaders and followers, who seek to incorporate into our articles of faith the principle of what has been interpreted by the public, as ‘free love.’”

She went on to state the true goals of suffrage: “A woman’s right to education — literary, artistic and scientific; her avocations — industrial, commercial and professional; her interests — percuniary, civil and political. In a word, her rights as an individual and her functions as a citizen.”

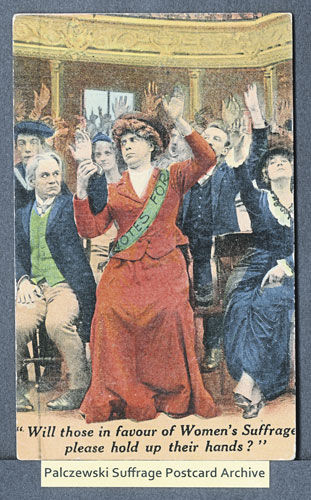

Propaganda appeared on both sides, each seeking to sway public opinion.

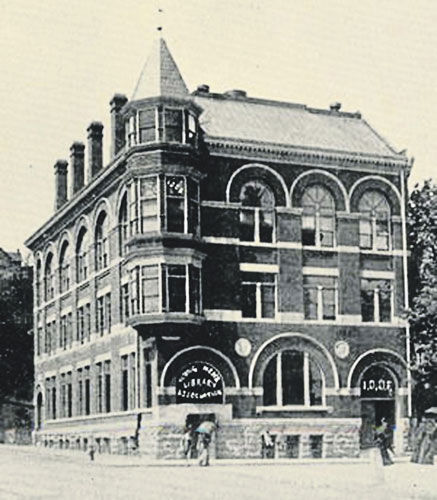

The Dubuque Ladies Literary Association was known for slipping propaganda into its monthly minutes. The group’s minutes detailed music, readings, refreshments and sometimes included seemingly unrelated tidbits, including this one about the women of ancient Sparta.

“May not woman, intellectually trained, give to her country something better? May they not go out from their homes sons and daughters with an earnest purpose in life … but to do battle for God, country and right against ignorance, infidelity and wrong?”

It sounded simple and rational. But suffragists were often considered to be radical, unreasonable and even insane.

After all of the opposition, Dubuque turned out to be a progressive county, bringing at least a partial right to vote to its female residents long before the 19th amendment was adopted.